How does COVID-19 coronavirus compare to the 1918 Spanish flu?

The world has seen outbreaks, with some worst than others, but one thing is common, all these outbreaks result in loss of life and a global health crisis. One of the worst epidemics in the world was the 1918 Spanish flu. Now, the current coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak is being compared to the Spanish flu that ravaged the world more than a century ago.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, the first of the two pandemics involving the H1N1 influenza virus, infected 500 million people across the world, and estimates suggest it killed anywhere between 17 and 50 million people.

Meanwhile, the current coronavirus outbreak has so far taken 3,996 lives and infected 113,582 people worldwide at the time of writing. COVID-19 cases are steadily increasing, with now more than 100 countries affected. China, South Korea, Italy, and Iran have the highest number of cases.

Health officials and scientists around the world are scrambling to contain the spread of the virus.

How does the coronavirus compare to the Spanish flu?

Pneumonia is the killer

Both infections can lead to pneumonia, which has been the culprit in many of the COVID-19 deaths. The type of pneumonia in COVID-19 is similar to that of the 1918 Spanish flu. However, the death rate form COVID-19 is many times lower than that of the 1918 Spanish flu.

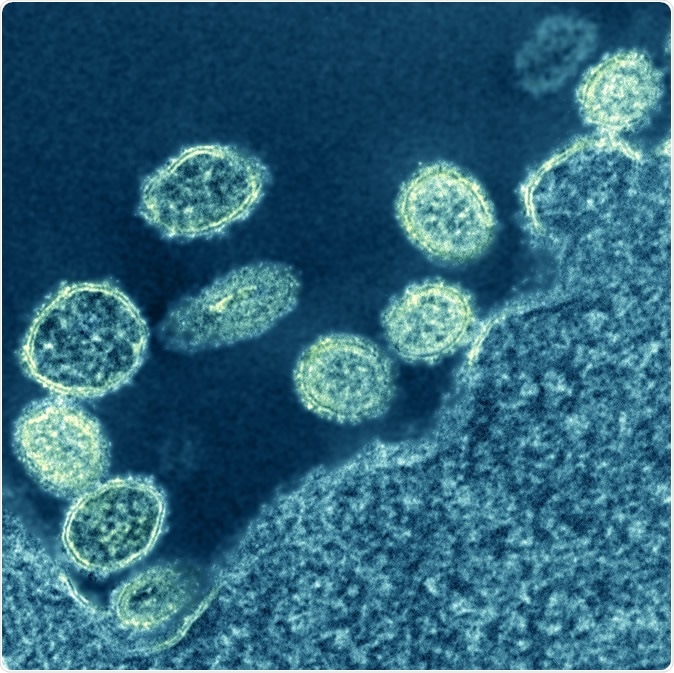

1918 H1N1 Virus Particles. Electron micrograph of 1918 H1N1 influenza virus particles near a cell. Credit: NIAID

Spanish flu and COVID-19 are both infectious respiratory illnesses, which share some symptoms. Both the infections cause fever, coughing, and sometimes, body aches. However, in Spanish flu, it caused nausea and diarrhea, not seen in patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, the lungs in patients with the Spanish flu were filled with a frothy and blood substance, causing suffocation with patients turning blue.

In COVID-19 patients, one of the pathognomonic signs is shortness of breath. The most common symptoms of this infection are fever, cough, which is usually dry, and shortness of breath, or difficulty of breathing.

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round gold objects) emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes COVID-19. The virus shown was isolated from a patient in the U.S. Credit: NIAID-RML

COVID-19 threatens older adults and immunocompromised people

COVID-19 usually targets those with weakened immune systems. Older people and those with compromised immune systems make up the majority of those who died from the disease. The China Centers for Disease Control has reported that most cases in the country, or 87 percent of all cases, were people between the ages of 30 and 79.

Younger adults, adolescents, and children may encounter or contract the infection, but they have milder symptoms or, in some cases, none at all. Based on the report, only 8.1 percent of cases were in people in their 20s, 1.2 percent were adolescents, and 0.9 percent were nine years old and younger.

On the other hand, the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 has an unusually high young adult mortality, affecting people young adults who are well and healthy. Hence, scientists have dubbed the pandemic as the “greatest medical holocaust in history.”

A study examined historical data tackling the high proportion of young people who were infected by the Spanish flu, implying that older people may have acquired immunity from an earlier influenza outbreak.

Spread was slower in the Spanish flu pandemic

The spread of the Spanish flu was more gradual as air travel was still a new mode of travel a century ago. The virus was spread via rail and sea rather than airlines. Some places had months and even years to prepare before the flu arrived in their countries. Historians have tied the spread of the Spanish flu to troops fighting in World War I.

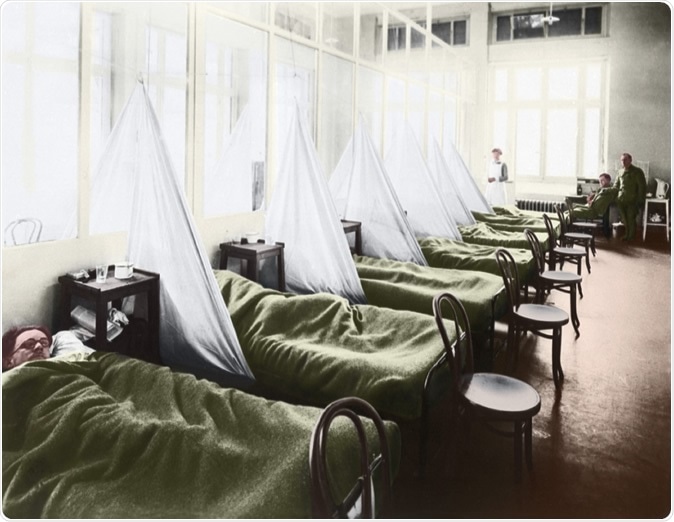

An influenza ward at the U S Army Camp Hospital in Aix-les-Bains France during the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-19, 1918 photograph with digital color. Image Credit: Everett Historical / Shutterstock

The COVID-19 is fast spreading because traveling is an everyday necessity today, with flights from one country to another accessible to most.

Some places did manage to keep the virus at bay in 1918 with traditional and effective methods, such as closing schools, banning public gatherings, and locking down villages, which has been performed in Wuhan City, in Hubei province, China, where the coronavirus outbreak started. The same method is now being implemented in Northern Italy, where COVID-19 had killed more than 400 people.

Fatality rate worse in Spanish flu

The 1918 Spanish flu has a higher mortality rate of an estimated 10 to 20 percent, compared to 2 to 3 percent in COVID-19. The global mortality rate of the Spanish flu is unknown since many cases were not reported back then. About 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population contracted the disease, while the number of deaths was estimated to be up to 50 million.

Better public health and modern innovations

The Spanish flu lasted for two years, and a vast majority of deaths happened occurred in the fall of 1918, while the second wave of the outbreak was caused by a mutated virus spread by a wartime troop movement.

During that time, public funds are mostly diverted to military efforts, and a public health system was still a budding priority in most countries. In most places, only the middle class or the wealthy could afford to visit a doctor. Hence, the virus has killed many people in poor urban areas where there are poor nutrition and sanitation. Many people during that time had underlying health conditions, and they can’t afford to receive health services.

Currently, amid the coronavirus outbreak, health care systems are intact in most countries. In developing countries, though healthcare systems are weak, there is the availability of doctors and healthcare workers as well as hospitals to cater to the patients.

Moreover, medical innovations are continually improving across the globe, with scientists and health experts racing to find a vaccine or a treatment for the novel coronavirus illness.

Sources:

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus). https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

- Chine Centers for Disease Control. (2020). http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51

- Gagnon, A., Miller, M., Hallman, S., Bourbeau, R., Herring, A., Earn, D., and Marinas, J. (2013). Age-Specific Mortality During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Unravelling the Mystery of High Young Adult Mortality. PLOS ONE. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3734171/

- Purple Death The Great Flu of 1918 - https://www.paho.org/English/DD/PIN/Number18_article5.htm

- Coronavirus: What can we learn from the Spanish flu? - https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200302-coronavirus-what-can-we-learn-from-the-spanish-flu

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario