Analyzing Tumor RNA May Help Match Patients with Most Effective Cancer Treatments

, by NCI Staff

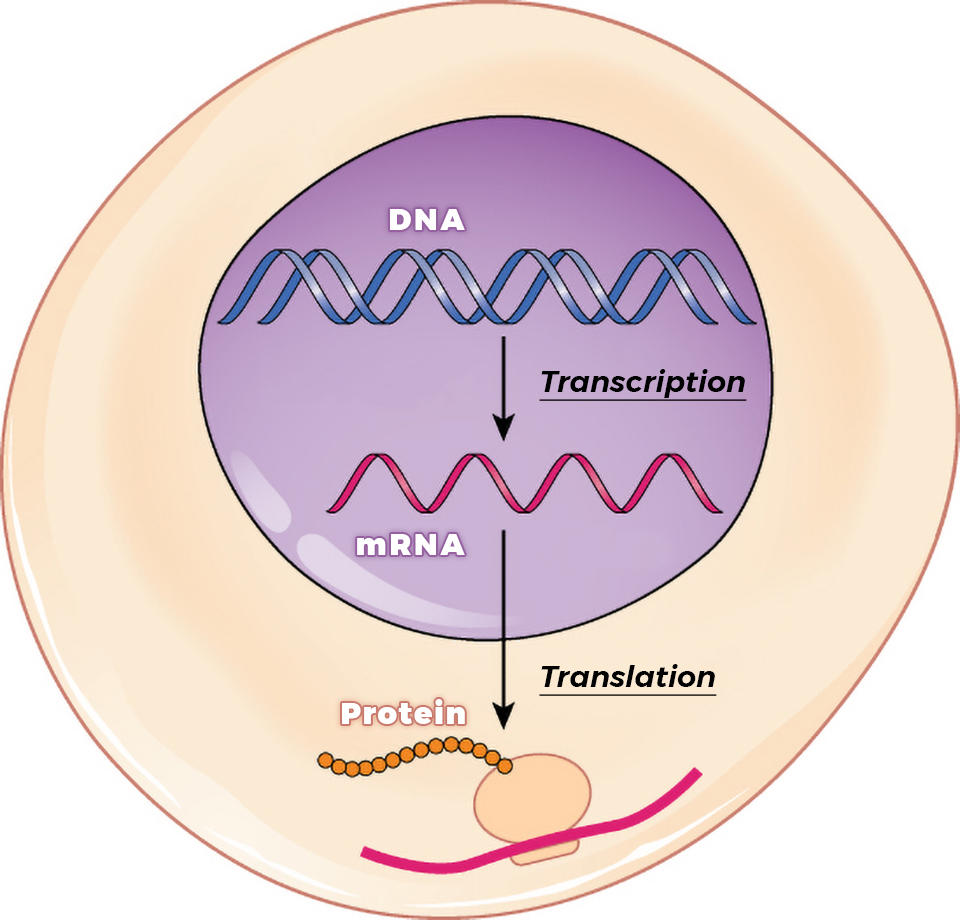

NCI scientists have crafted a novel approach to analyzing tumors that they say has the potential to bring precision cancer medicine to more patients. The new approach is based on analyzing gene expression in patients’ tumors. Gene expression is measured by examining levels of RNA, the molecular cousin of DNA.

In contrast, most precision medicine approaches in current clinical use are based on the analysis of alterations in DNA (such as mutations) in a few hundred genes.

“There have been some big wins with the [DNA-based] approach,” said study investigator Kenneth Aldape, M.D., chief of NCI’s Laboratory of Pathology. But “while worthy of pursuit, those successes are few and far between.”

Although RNA-based tests for gene expression have the potential to improve precision medicine, it has been challenging to translate gene expression data into information that is helpful for treating patients, said the study’s leader, Eytan Ruppin, M.D., Ph.D., chief of NCI’s Cancer Data Science Laboratory.

“What’s exciting is it’s the first time we’ve come up with a way to do that systematically, and then comprehensively test it,” Dr. Ruppin added.

The NCI researchers showed that their approach could accurately predict whether patients had responded to previous treatment with targeted therapy or immunotherapy. By reanalyzing data from a recent clinical trial that matched patients to treatment based on gene expression information, the researchers estimated that their approach could match far more patients to beneficial treatments than the level that was attained in that study.

But to learn more about its potential usefulness, the new approach still needs to be carefully tested in patients who haven’t already been treated and who are followed forward in time, Drs. Ruppin and Aldape both noted.

NCI researchers are now gearing up to gradually incorporate the new approach into the care of patients at the NIH Clinical Center. These efforts will complement DNA-based approaches that are already in place.

The study findings were shared February 17 on bioRxiv, a free online archive where scientists can make their findings immediately available to the scientific community. Articles in the archive have not been peer reviewed, meaning they have not been evaluated for quality and accuracy by experts. A more detailed report of the study has been submitted for peer review and publication.

Predicting Responses to Targeted Therapy

There are between 20,000 and 25,000 genes in the human genome, and they have complex relationships with one another. For cancer cells, some relationships between genes help the cells survive, while others are harmful.

These relationships can influence the effect that a drug has on a person’s cancer. For instance, a therapy that targets the mutated form of “gene A” may only work in patients whose tumors also have low expression of “gene B.”

Understanding interactions like those could help doctors choose the best treatments for individual patients. But it has been a huge challenge to identify such interactions because there are a staggering 500 million possible gene-pair combinations in the human genome, Dr. Ruppin explained.

Over the past several years, he and his colleagues have developed computational tools that use gene expression information to infer relationships between pairs of genes, focusing on genes that are hit by targeted therapies or immunotherapies. For the new study, they used these tools to analyze publicly available data sets containing molecular data from hundreds of patients and search for interactions across the entire genome.

“All the work that we are doing has been enabled only recently thanks to projects [that were] initiated, funded, or led by NCI, primarily The Cancer Genome Atlas,” Dr. Ruppin said.

Using data from 21 clinical trials of different targeted therapies, their approach accurately predicted patients’ responses to treatment in 17 out of 21 data sets. These data sets cover several different types of cancer and more than a dozen different kinds of targeted therapies.

They used a similar approach to predict the responses of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. In 7 out of 10 data sets, their approach accurately predicted whether patients responded to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

While their approach wasn’t accurate all the time, “there is a clear signal that it can be potentially useful for patients,” Dr. Ruppin said. With further testing, the team hopes that they will be able to learn more and improve the approach, he noted.

Comparing the New Approach to the WINTHER Trial

Next, the researchers pitted their approach against one used in a recent precision medicine trial of patients with cancer that had gotten worse after treatment with standard therapies.

For the trial, called WINTHER, clinicians matched patients to treatment based on the DNA alterations or RNA levels in the patients’ tumors. The RNA-based approach was only used for patients who didn’t have any tumor DNA alterations that could be matched to a treatment.

As the first clinical trial to use RNA data to influence cancer treatment decisions, the WINTHER study was a major advance, Dr. Aldape said.

The RNA approach used by the WINTHER investigators was based on the expression in patients’ tumors of the gene or genes targeted by each drug used in the trial. Among 86 participants who were treated based on this RNA approach, 23 (27%) responded to the treatment.

But how many patients would have benefited if the treatment choices were guided by the NCI team’s approach?

The NCI researchers used their approach to determine which of 32 FDA-approved targeted cancer therapies would work best for each patient. If the treatments had been selected by their approach, 74 patients (86%) would have responded, they estimated.

However, taking potential false-positive test results into account, a more realistic estimate would be around 60%, Dr. Ruppin said.

Testing the Approach at the NIH Clinical Center

The team’s approach is slowly making its way into use at cancer clinical trials being conducted at the NIH Clinical Center. NCI leaders are cautiously considering how best to incorporate the approach into the care of patients at the Clinical Center.

Dr. Ruppin and his colleagues are also collaborating with other clinicians at NCI to plan a randomized clinical trial of the new approach. The trial will help address questions about whether the approach is reliable and benefits patients, Dr. Aldape explained.

The goal, he said, is to “gradually and carefully learn more about the potential benefits of our approach.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario