The Brain and Schizophrenia

Scientists have long tried to find out what was going wrong in the brains of people with schizophrenia, but with so little success for so long that for some years the popular saying among specialists was that "schizophrenia is the graveyard of neuropathologists."

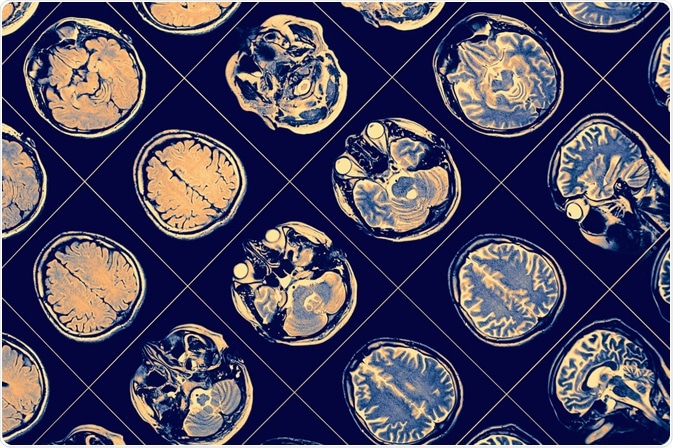

The advent of brain imaging using computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the 1980s led to renewed interest in finding abnormalities in brain structure.

Combining findings from cerebral imaging with molecular genetics and the study of abnormalities in cerebral structure, researchers hope to uncover what causes the symptoms of this disease.

Image Credit: sfam_photo/Shutterstock.com

What Macroscopic Changes Are Seen in The Schizophrenic Brain?

It was more than a century ago that E. Kraepelin put forth the theory that schizophrenia was due to underlying disease of the brain structure. Alzheimer's and others went on to find that patients with psychosis did not show the presence of gliosis in their brains.

In other words, the impact on the brain was not significant enough to reduce the number of brain cells in the fully grown brain, unlike the brain of dementia patients.

The following changes seem to be prevalent among schizophrenic patients, and are progressive, as proved by different research studies:

- Lower overall cortex volume

- Enlargement of lateral and third ventricles

- Presentation of these findings in patients with first-episode schizophrenia

- Temporal lobe shrinkage including the hippocampus

- Lower thalamic volume

- Gray matter lost rather than white matter

- Patients on antipsychotic drugs show enlargement of the basal ganglia

The volume changes in schizophrenic brains are due to the inadequate development of the cell bodies and processes of the neurons, such as dendrites and axons.

Synaptic organs, as well as synaptic markers, have been reported to be lower than normal. Such abnormalities are linked to the global failure of normal synaptic transmission.

Microscopic and Biochemical Changes

Histologic examination shows that gliosis is absent, while the neurons in the hippocampus and cortex are smaller than normal. The number of neurons in the dorsal thalamus is reduced. Synaptic and dendritic marker proteins are also reduced in schizophrenia. The distribution of white matter neurons may be abnormally distributed.

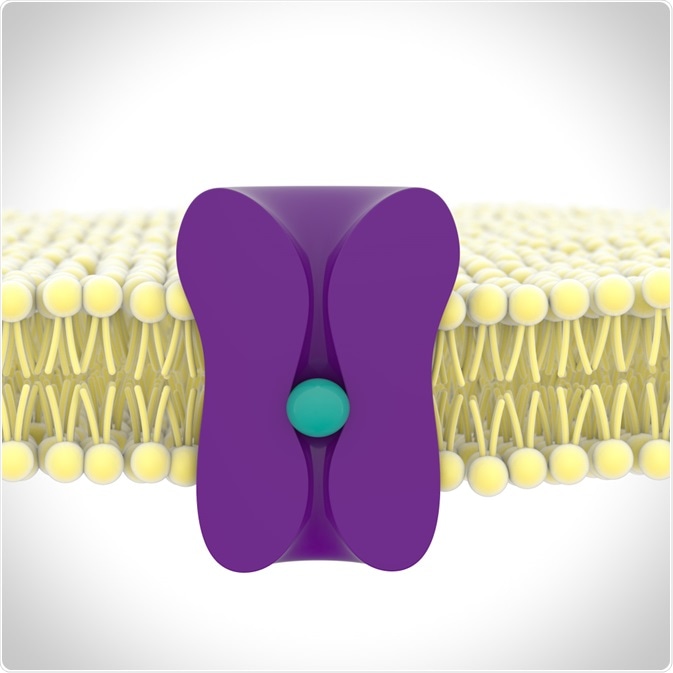

The abnormal brain also shows an impaired expression of non-NMDA receptors and a higher number of NMDA receptors (NMDAR). Glutamate reuptake is higher in the frontal lobe.

NMDAR activation causes the influx of calcium ions which in turn results in the synthesis of synapse-altering proteins via the CREB pathway, which is required for memory formation by long-term potentiation. This is thus related to synaptic plasticity, which in turn is linked to neurodevelopment and neuroplasticity.

Recent research has also shown the build-up of abnormal protein in the brains of schizophrenic patients.

About half of the brains from such individuals showed excessive content of indissoluble protein, indicating abnormal misfolded protein, as well as higher levels of ubiquitin, a small protein that accompanies protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disorders.

Image Credit: sonorileto/Shutterstock.com

Is Schizophrenia A Genetic Condition?

Along with imaging, sophisticated gene analysis has led to the finding of several genes that increase the risk of schizophrenia. Several of these genes like DISC1, NRG1, RGS4, and dysbindin are linked to the development and maturation of nerves, and the creation of networks of nerves.

It is thought that multiple genes may interact to predispose towards schizophrenia.

Are These Changes Inherent or Medication-Related?

The continuum of brain volume changes observed by neuroimaging, and the appearance of brain structural anomalies over time in schizophrenic patients, has led to the further hypothesis that neurons degenerate in this condition.

This may account for the initial presentation with hallucinations and delusions, or positive symptoms, followed by the slower presentation of low motivation, and reduced participation in social interactions, called negative symptoms.

A rat model showed that the changes in the schizophrenic brain were not due to antipsychotic medication. Mass spectroscopy showed that these proteins were linked to the development of the nervous system, especially in neurogenesis and synapse formation.

The detection of brain changes by advanced imaging techniques along with the absence of gliosis led in due time to the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. In other words, the change in brain morphology occurs during early brain development, in the fetal period.

Reports that learning and social brain function, as well as an abnormality of motor functions, are seen to be reduced before the earliest mental symptoms, support this theory.

Physical anomalies like a lower head circumference at birth are also much more common in individuals with schizophrenia.

Moreover, the odds ratio for schizophrenia to develop in individuals with any type of perinatal abnormality, or with low birth weight, is 2 and 2.6, respectively. Fetal infections could also have a direct effect on brain development.

Scientists now think that the original abnormality in brain development is followed by a loss of normal adaptability or what is called neuroplasticity, the ability to adapt to a loss of function in some part by compensatory training of another part.

The effect of antipsychotic drugs on the brain is also a moot point, as such drugs have been reported to increase the frequency of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain compared to similar brains without such exposure.

However, very little is known about how long-term antipsychotic therapy affects the brain.

The Two-Hit Theory

Researchers have the two-hit theory that has been proposed, with the first hit being the genetic weakness with the superadded insult occurring during fetal life, leading to abnormal brain development. This is only the foundation for the potential development of schizophrenia.

In later life, as in adolescence or early adulthood, the occurrence of psychological stressors (“the second hit”) tips the balance, causing the emergence of schizophrenia symptoms.

With repeated episodes followed by quiescent periods, negative symptoms arise. These are considered to be the result of neurodegeneration, which is the source of the findings in imaging studies.

Recently, psychiatrists have come to believe that a third hit also operates to speed up the further progression of the disease.

This is the failure to intervene appropriately in the early or critical stages of the disease which may mean missing a chance to alter the outcome of the disease process.

Future Directions

John Hopkins researchers have found how to use neuron samples from the nose in living individuals as substitutes for brain biopsies.

Newer studies exploiting this technique could help reveal if abnormal protein accumulation is linked to the symptoms in a dose-dependent manner, and if so, how.

References and Further Reading

- Iritani, S. (2013). What Happens in The Brain Of Schizophrenia Patients? An Investigation From The Viewpoint Of Neuropathology. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science v.75(1-2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4345712/

- DeLisi, L. E. et al. (2006?). Understanding Structural Brain Changes in Schizophrenia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience; 8(1): 71–78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181763/

- Vuong, Z. (2017). Schizophrenia Found to Disrupt the Brain’s Entire Communication System. Available at: https://news.usc.edu/127835/schizophrenia-disrupts-the-brains-entire-communication-system-researchers-say/. Accessed on 4 April 2020.

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 4, 2020

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario