Acalabrutinib Receives FDA Approval for Mantle Cell Lymphoma

December 12, 2017, by NCI Staff

On October 31, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to acalabrutinib (Calquence®) for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma whose cancer has progressed after receiving at least one prior therapy.

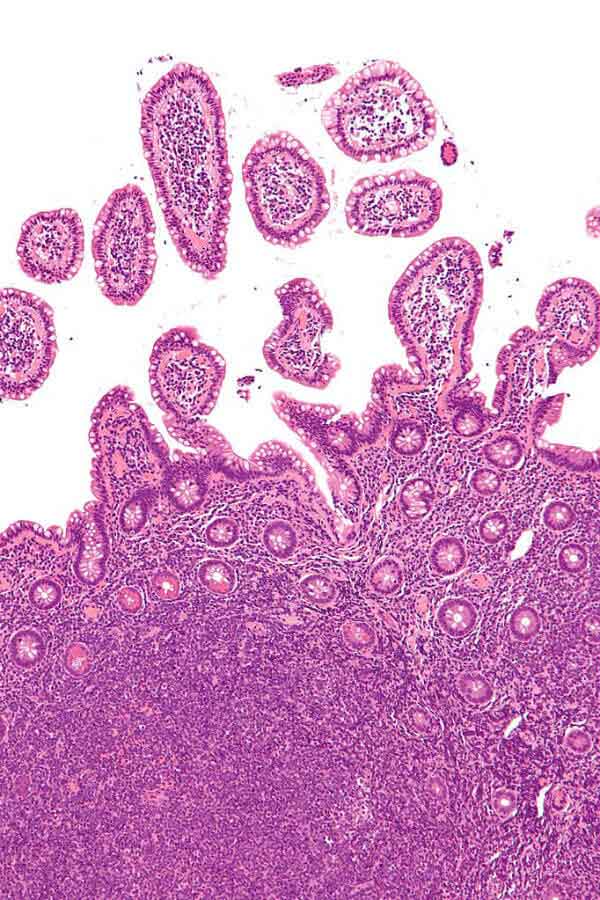

Mantle cell lymphoma is a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that arises in B cells, a type of white blood cell. Most people with mantle cell lymphoma are diagnosed with aggressive, widespread disease. Unlike some other types of aggressive lymphomas, however, mantle cell lymphoma is rarely curable with current therapies.

Even if the initial treatment works, the disease comes back in virtually all patients, explained Wyndham Wilson, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

How long it will take to relapse, and how long a second response may last, depends largely on the patient’s response to the initial course of treatment and the biology of their disease, which can vary greatly from patient to patient, Dr. Wilson said.

Second-Generation BTK Inhibitor

Acalabrutinib is a targeted drug that interferes with a protein called Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), which is essential for B-cell development.

In 2013, FDA approved the first BTK inhibitor, ibrutinib (Imbruvica®), for patients with relapsed or refractory (treatment-resistant) mantle cell lymphoma. Acalabrutinib is a second-generation BTK inhibitor that “distinguishes itself from ibrutinib theoretically and in laboratory studies by being more specific," Dr. Wilson said. In other words, acalabrutinib does not appear to inhibit other tyrosine kinases that don't seem to be necessary for its action against mantle cell lymphoma.

"Because of that, studies suggest, but have not proven, that its side-effect profile may be somewhat improved over ibrutinib,” he explained.

Both ibrutinib and acalabrutinib can cause problems with bruising and bleeding, but acalabrutinib may be less likely to do so, Dr. Wilson continued.

Ibrutinib also causes problems associated with atrial fibrillation, and studies suggest that atrial fibrillation may be less likely with acalabrutinib, Dr. Wilson explained.

“Those are two unwanted side effects with ibrutinib that studies suggest acalabrutinib may be less likely to cause, but I say ‘suggest’ for two reasons," he said. "One, no one has done a head-to-head study of the two drugs, and two, there’s a lot less [clinical] experience with acalabrutinib.”

So although acalabrutinib seems to be as effective as ibrutinib in hitting BTK, it may be safer, at least theoretically. "We won’t know if it is truly safer until we have more experience with it,” he said.

High Response Rates, Durable Responses

FDA based its approval on data from a single-arm clinical trial of 124 patients with mantle cell lymphoma whose cancer had progressed or returned after at least one prior treatment regimen. All the patients received acalabrutinib. The trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca, which manufactures acalabrutinib.

In the trial, 81% of patients experienced a clinical response to treatment, with responses split almost evenly between partial responses (41%) and complete responses (40%). After 15.2 months of follow up, the median duration of response had not been reached.

Common side effects among trial participants included low blood cell counts, diarrhea, muscle pain, and bruising. Serious side effects included neutropenia, anemia, infections, and irregular heartbeat.

About 8% of trial participants either had dose reductions or discontinued treatment because of adverse side effects.

“The key to acalabrutinib’s approval is twofold,” said Michael L. Wang, M.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the trial’s principal investigator. “One, it is another potent [BTK] inhibitor that has made a substantial improvement in patient care. And two, this drug seems to have a different side effect profile compared with ibrutinib, so those who are intolerant of one inhibitor may be able to try the other.”

Dr. Wang presented the results from the trial on December 9 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in Atlanta.

An Incremental Improvement

Although they hit the same target, ibrutinib and acalabrutinib have some important differences.

In addition to its greater selectivity in targeting BTK and its potentially better safety profile compared with ibrutinib, acalabrutinib capsules are approved to be taken twice a day, whereas ibrutinib is approved as a once-a-day capsule. Laboratory studies have suggested that this twice-daily dosing may more effectively inhibit BTK over the course of therapy, Dr. Wilson explained.

“If that’s the case, then maybe its utility will be somewhat improved over ibrutinib, which may not inhibit BTK as robustly over the 24 hours that you’re giving the drug,” he said. “So, there’s a sense that maybe treatment with acalabrutinib will lead to more durable responses.”

Much more clinical experience with acalabrutinib is needed, though, to determine its role in treating mantle cell lymphoma, Dr. Wilson stressed.

“I wouldn’t call it a game changer, but I would say acalabrutinib holds promise to be an improvement—but an incremental improvement—over the first-generation BTK inhibitor,” he said.

Under FDA’s accelerated approval rules, AstraZeneca is required to complete additional studies to confirm that acalabrutinib has clinically meaningful benefits for patients. The company is currently recruiting patients for a phase 3 clinical trial to test acalabrutinib in combination with bendamustine and rituximab (Rituxan®) in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario