Compelling New Evidence Further Suggests Parkinson’s Disease Begins in the Gut

A new mouse study has revealed more evidence that Parkinson’s disease originates in the gut before traveling to the brain via the body’s neurons.

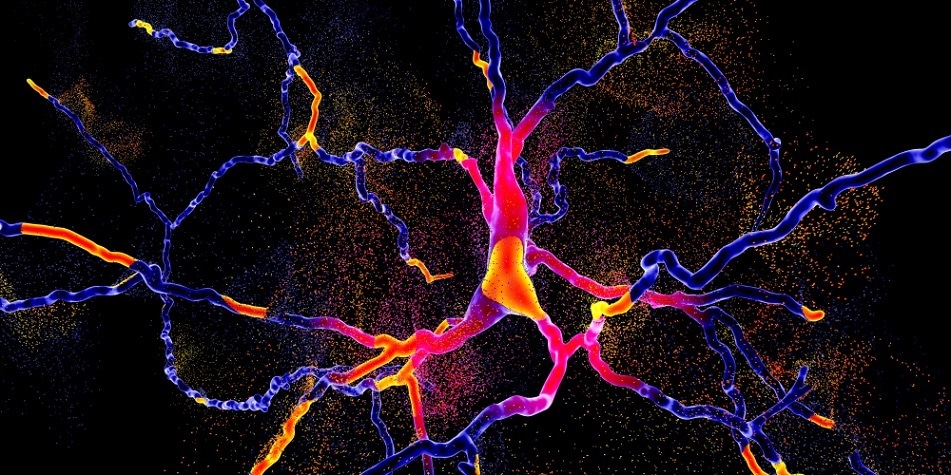

Shutterstock | Kateryna Kon

Published in the journal Neuron in June 2019, the study carried out by Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers used mice to obtain more accurate methods with which to test Parkinson’s treatments that could impede disease progression.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological condition in which the brain becomes damaged due to a loss of nerve cells in the part of the brain called the substantia nigra. A reduction in the levels of dopamine is responsible for a number of the symptoms that characterise the condition, which include involuntary tremors, slow movement, and stiff muscles. Psychological symptoms can also be present and include depression, anxiety, and problems with memory and balance.

It’s also believed that Parkinson’s disease is caused by a build-up of a misfolded protein alpha-synuclein in the brain cells. Due to large amounts of the protein binding together, nerve tissues die and cause an accumulation of dead brain matter called Lewy bodies. Loss of movement and cognitive problems are caused by this loss of brain cells.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease usually only present themselves when approximately 80% of the nerve cells in the substantia nigra have been lost, however the exact reason why nerve cells are lost has not been determined. Current research suggests that genetic changes and certain environmental factors may trigger the development of the disease.

It was a 2003 Parkinson’s study by German neuroanatomist Heiko Braak that showed the accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein protein in parts of the central nervous system that control the gut.

Hanseok Ko, PhD, associate professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of medicine said that the accumulation of alpha-synuclein protein tied in with the early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease such as constipation. In Braak’s study, he suggested that Parkinson’s disease travelled through the nerves connecting the gut and the brain, likening the process to climbing a ladder.

For this new study, researchers injected 25 µg of synthetic misfolded alpha-synuclein protein into the gut of healthy mice. After one, three, seven, and 10 months after the injections, researchers took samples and analyzed the mouse brain tissue. Over the period of 10 months, the researchers found evidence that the alpha-synuclein protein began to accumulate where the vagus nerve connected to the gut and then spread throughout the brain.

The experiment was in response to mounting evidence already suggesting that Parkinson’s disease is developed in the gut and travels to the brain, where the neurological damage then commences.

The researchers focused on whether the misfolded proteins were able to travel along the vagus nerve, commonly known as the 10thcranial nerve, the longest and most complex of the cranial nerves. The vagus nerve extends from the brain through the face and thorax to the abdomen, and its esophageal branches control the involuntary muscles in the stomach and small intestine, among others.

After their initial experiment the researchers surgically cut the vagus nerve in one group of mice and injected their guts with misfolded alpha-synuclein. After seven months, the researchers examined the mice and found that those with a cut vagus nerve showed no signs of cell death when compared to mice that had not had their vagus nerve cut.

Dawson explained that the cut vagus nerve appeared to stop the progression of the misfolded protein towards the brain.

Behavioral changes linked to the severed vagus nerve in the mice were also investigated, splitting the mice into three groups: mice injected with the misfolded protein, mice with a cut vagus nerve and injected with misfolded protein, and control mice who did not undergo any injections or surgical severing of the vagus nerve.

Nest-building and exploring new environments are typical mouse behaviors that are studied when identifying Parkinson symptoms in the species.

Initially, the researchers found that mice who were injected with misfolded alpha-synuclein protein were less able to build good nests seven months later, which suggests there has been some damage to motor control. Their ability to build nests was scored on a scale of zero to six, and mice with misfolded proteins produced consistently lower scores when compared to healthy mice.

Mice with the misfolded protein scored lower than one, while the group of mice with a cut vagus nerve and the control group often scored three or four when building nests. Interestingly, most mice used all of the 2.5 g of nesting material given to them. However, mice injected with the misfolded alpha-synuclein protein used less than half a gram of nesting material. This this suggested that the mice’s fine motor control abilities were worsening in line with disease progression, as explained by Ko.

A third experiment showed that healthy mice placed in a large open box were more open to exploring their new environment, whereas mice with misfolded alpha-synuclein showed higher levels of anxiety and were less likely to stray far from the corners of the box. This experiment was to analyze symptoms often seen in humans, which sees anxiety levels increase with disease progression.

Mice with severed vagus nerves spent between 20 and 30 minutes exploring the new environment, especially in the centre of the box. However, mice with alpha-synuclein injections whose vagus nerves were left intact spent under five minutes exploring the central areas of the box, opting to stay close to the edges instead.

The study proves that misfolded proteins can be transmitted from the gut to the brain in mice, using the vagus nerve as its route to the brain. By cutting the vagus nerve, Parkinson’s disease symptoms were dramatically reduced, and this could prove instrumental in preventing the neurological decline characterizing the disease.

“This is an exciting discovery for the field and presents the target for early intervention in the disease,” Dawson said.

The next steps in the research include exploring which part of the vagus nerve enable the misfolded proteins to travel to the brain, as well as investigating methods to prevent this from happening.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario