03/30/2017 | |

Patients with previously treated acute lymphoblastic leukemia who received blinatumomab, which encourages the immune system to kill cancer cells, lived longer and experienced fewer side effects than patients given standard chemotherapy. | |

Blinatumomab Extends Survival for Patients with Advanced ALL

March 30, 2017, by NCI Staff

Patients with advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who received an immunotherapy drug called blinatumomab (Blincyto®) lived longer than patients who received standard chemotherapy regimens, according to results from a phase III randomized controlled trial.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) previously granted blinatumomab accelerated approval for the treatment of advanced ALL based on promising results from smaller early-phase trials. The results of the larger phase III trial confirmed these earlier findings.

Patients in the trial had already undergone many treatments prior to enrolling, explained Richard Little, MD, of NCI's Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, making it "pretty remarkable that a survival advantage was seen,” he commented. “And even though it was a small survival advantage, I think that points to the importance of developing this agent [for use] as part of the treatment when ALL is first diagnosed.”

The results were published March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Better Results with Fewer Side Effects

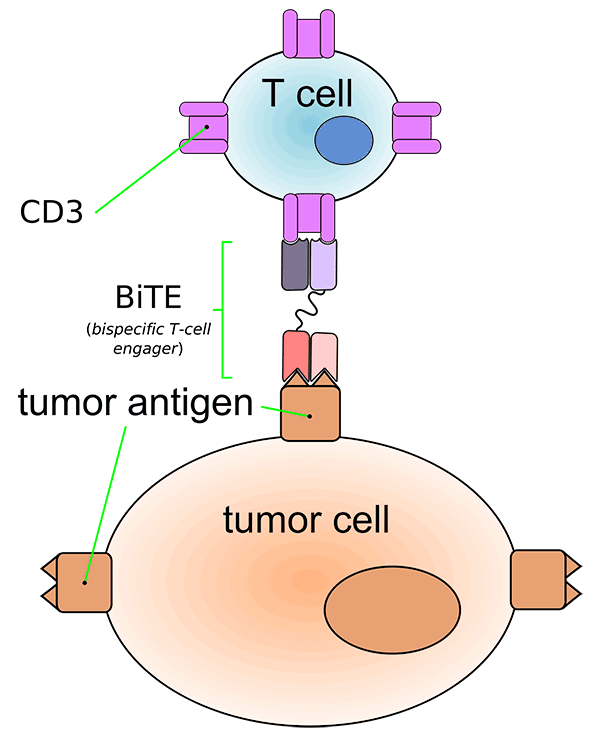

Blinatumomab is a type of immunotherapy called a bispecific monoclonal antibody. These drugs bind to two different molecules at the same time. The two molecules to which blinatumomab binds are a protein (CD19) expressed on the surface of ALL cells and a protein (CD3) expressed on immune system cells called T cells. The bridge formed by blinatumomab brings the T cells close enough to the ALL cells to recognize and kill them.

The current clinical trial included 376 patients with ALL that had recurred—in some cases many times—or had not responded to standard treatments.

The trial investigators, led by Hagop Kantarjian, M.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, randomly assigned participants to receive blinatumomab or standard chemotherapy with any of four chemotherapy regimens. If their disease responded to any of the initial treatments, participants could receive up to a year of maintenance therapy with that treatment.

In early 2016, the trial was stopped early because of the survival advantage observed for patients in the blinatumomab group. Median overall survival was 7.7 months for patients in the blinatumomab group, compared with 4.0 months for patients in the chemotherapy group. Patients who received blinatumomab were also more likely to experience a complete remission with no cancer cells found in the bloodstream (34% versus 16%).

Patients in the blinatumomab group had slightly fewer grade 3 (severe) adverse effects overall than patients who received chemotherapy (87% versus 92%). In earlier trials of blinatumomab, more than 10% of patients experienced a potentially life-threatening side effect called cytokine release syndrome, where severe inflammation spreads throughout the body.

Based on what researchers learned from those trials, explained Dr. Little, they changed the way the drug is administered to a gradual, continuous infusion given over 4 weeks, reducing the risk of cytokine release syndrome. Currently, side effects from blinatumomab “are generally minor and amenable to management with steroids and [treatment] interruptions,” said Dr. Kantarjian.

“As a single agent, blinatumomab is superior to standard chemotherapy, and less toxic,” he said. “So the question is now, what do we do next?”

More Trials for ALL

“The real power of this study is that it gives a strong rationale for pursuing this drug in earlier phases of disease—even in the upfront, previously untreated setting—and combining it with other novel therapies,” commented Dr. Little. A clinical trial testing blinatumomab as part of treatment for newly diagnosed patients is currently underway, he added.

“I think the really interesting research in this area is how to combine it most optimally with other therapies,” he continued. Another agent, an antibody-drug conjugate called inotuzumab, which targets a different molecule (CD22) on the surface of cancer cells than blinatumomab, has also shown positive results in a large phase III trial, so testing the two drugs together holds promise, said Dr. Little.

Other studies should also investigate the efficacy of blinatumomab combined with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed patients, commented Dr. Kantarjian.

“We’re able to cure 40%–50% of adults with ALL, but this is at the expense of very intensive chemotherapy that lasts for an average of 3 years,” explained Dr. Kantarjian. He hopes that adding immunotherapy to first-line chemotherapy could reduce the severity and length of initial treatment, to perhaps less than a year, and increase the cure rate at the same time.

Other types of immunotherapies, such as CAR-T cells and immune checkpoint inhibitors, are also being tested in leukemia, added Dr. Kantarjian.

“These are all getting into the arena of leukemia therapy, with very encouraging results,” he concluded.

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario