NCI’s Technology Transfer Center—Moving Inventions and Ideas from the Lab to Patients: An Interview with Dr. Michael Salgaller

July 17, 2017, by NCI Staff

Last month, NCI held its inaugural Technology Showcase in Frederick, Maryland. The event brought together researchers and administrators from NCI and the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research(FNLCR) with investors, representatives from industry and nonprofit organizations, and government officials. The event, which the NCI Technology Transfer Center(TTC) and FNLCR helped organize, showcased technologies being developed at NCI and FNLCR and encouraged startup company formation, technology licensing, and collaborations.

In this interview, Michael Salgaller, Ph.D., who leads the TTC’s Invention Development and Marketing Unit, discusses the center’s efforts to move new technologies developed by NCI and other NIH scientists from the lab to the patient’s bedside.

Can you tell us a bit about the history and the goals of the NCI Technology Transfer Center (TTC)?

The TTC was established after a federal law passed in 1980, known as the Bayh–Dole Act, which allowed federally funded research to be licensed by outside parties.

Our goal is to advance the development of inventions and technologies that NCI and other NIH researchers come up with, into products that help patients, advance research, and spur economic development. In addition to working on behalf of NCI researchers, our TTC also helps nine other smaller NIH institutes and centers that do not have their own TTCs, with their technology transfer activities.

Why is the center’s work important for supporting the cancer research enterprise?

NCI cannot directly commercialize inventions. It takes an industry partner and resources to have a medical product approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before it is marketed, sold, and administered to patients. The only way that we can get a technology from the bench to the bedside is by working with industry partners to take medical solutions across the finish line.

What types of technologies or products does the TTC handle?

NCI is mostly known for developing new therapeutics, but we also invent medical devices and diagnostics. We’re also doing more and more work in digital health and health information technology, and there’s a lot of patient and industry interest in getting those types of technologies to patients.

What are some recent TTC success stories that are helping people with cancer?

TTC played a key role, along with other groups within NCI, in commercializing dinutuximab (Unituxin®), the first FDA-approved therapy for children with high-risk neuroblastoma.

Through the NIH Clinical Center, NCI also brings to the table the expertise needed to take a discovery and further develop it by conducting clinical studies in patients. The most recent example is avelumab (Bavencio®), an immunotherapy drug that has received FDA approval for two indications and is being tested in multiple clinical trials for other types of cancer. The first FDA approval of avelumab was for Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare type of skin cancer for which there was previously no treatment.

What sorts of activities are involved in completing a typical technology transfer agreement?

We work with the company, or with other organizations, such as academic or nonprofit organizations interested in licensing or collaborating on NCI inventions, to determine which type of legal agreement is best for the type of project that they are pursuing.

For instance, companies sometimes have research activities or products under development that are known only to the company and its investors. We can execute a nondisclosure agreement that promises that we will keep confidential anything they tell us about their activities that is not public knowledge.

We can help to manage everything from the filing of an employee invention report to the patenting process and all the different agreements we may have with partners as a technology is being developed and licensed.

What types of agreements does TTC facilitate?

The type of joint research that led to avelumab’s approval uses a type of technology transfer known as a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement, or CRADA, which allows the outside company and NCI to collaborate. If new intellectual property (IP) is created out of joint clinical research, the TTC works with both parties to make sure that the new IP is patented and to facilitate any other research agreements that are needed to further those new discoveries. The CRADA provides the industry partner with legal rights to elect an option to exclusively license new inventions.

Other agreements may be used instead of or along with CRADAs and licenses. These include Confidential Disclosure Agreements (CDAs), which protect confidential information. Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs) allow NIH to exchange materials (for example, cell lines) with extramural researchers. Clinical Trial Agreements (CTAs) allow NIH to receive investigational drugs for clinical trials. Collaboration Agreements are commonly used for more exploratory joint research projects with universities or industry.

What volume of agreements does TTC handle?

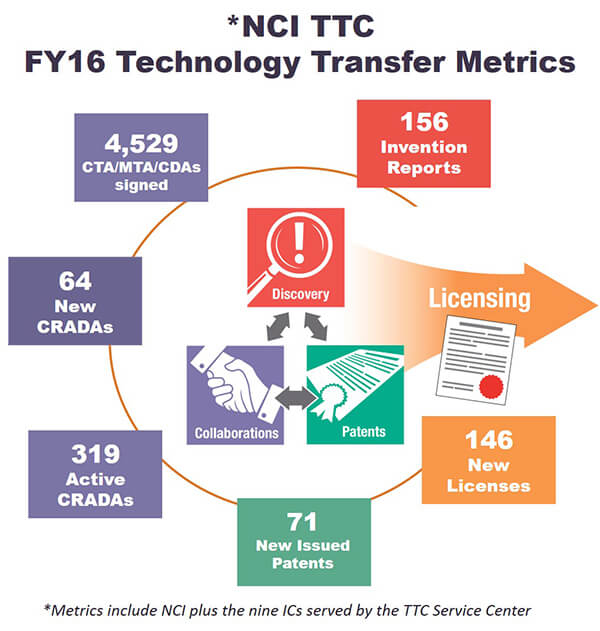

In fiscal year 2016, TTC negotiated or executed 146 new licenses; 71 patents; 64 new CRADAs; 4,529 CTAs, MTAs, and CDAs; and 156 invention reports.

The take-home message from such statistics isn’t just the amount and quality of work carried out every day by knowledgeable technology transfer professionals. It underscores that NIH isn’t bureaucratic and difficult to deal with, despite being the largest research institute in the world. It also shows that we can help guide the extramural community to address health issues affecting the quality and quantity of people’s lives.

What are some of the challenges involved in commercializing the research of NCI and other NIH scientists?

Because of Department of Health and Human Services regulations, NIH investigators have limited ability to be involved in further developing the technology once it leaves their laboratory. By contrast, if an NIH-funded extramural investigator (that is, someone who conducts research outside NIH) comes up with an idea for a new drug or technology and wants to start their own company, they may be allowed to be an entrepreneur while also keeping their position.

Another challenge is that a lot of NIH research is basic or preclinical research, and companies and investors prefer to work with a technology that has at least some proof-of-concept data from human studies.

For example, if you have a drug that cures cancer in mice, that doesn’t necessarily mean it will help a person suffering from that cancer. Developing medical solutions takes a long time and is very costly, and so the earlier a technology is in the development pipeline, the longer and more expensive the path forward. Basic and pre-clinical research still leads to important medical breakthroughs, such as Gardasil, the first preventive cancer vaccine (against cervical cancer), so we try to generate commercial interest in earlier-stage innovations as well.

Also, many companies developing medical solutions simply don’t know that it is possible to collaborate and work with NIH in moving their ideas and inventions—as well as those of our investigators—to patients.

Are the services that the TCC provides more in demand now than they were in the past?

Yes, because more and more companies are using technologies developed externally to augment their product pipeline. In addition, we’re doing a huge amount of outreach, including on an international level, to spread the word that we have great investigators and inventions that are available for collaboration or licensing.

In the past, NCI scientists with technologies available for partnering and licensing might have put that information on a website and hoped that someone might find it. Now, we are actively seeking partners and letting them know that we have a team of professionals who can break down the silos and can overcome the reluctance to work with government because of perceived bureaucracy. By taking this proactive approach, NCI hopes to decrease the time from when an invention is discovered to when it can be developed and become a product that can benefit patients.

Tell us more about the recent Technology Showcase cosponsored by NCI and FNLCR.

This event was the first of its kind in stressing the commercialization potential of the technologies developed by NCI and FNLCR scientists, rather than having science talks focused solely on the technologies themselves. The event provided great exposure for our scientists and their inventions, and it has generated interest in new licensing and other agreements.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario