Alternate Driver of Treatment-Resistant Prostate Cancer Identified

November 14, 2017, by NCI Staff

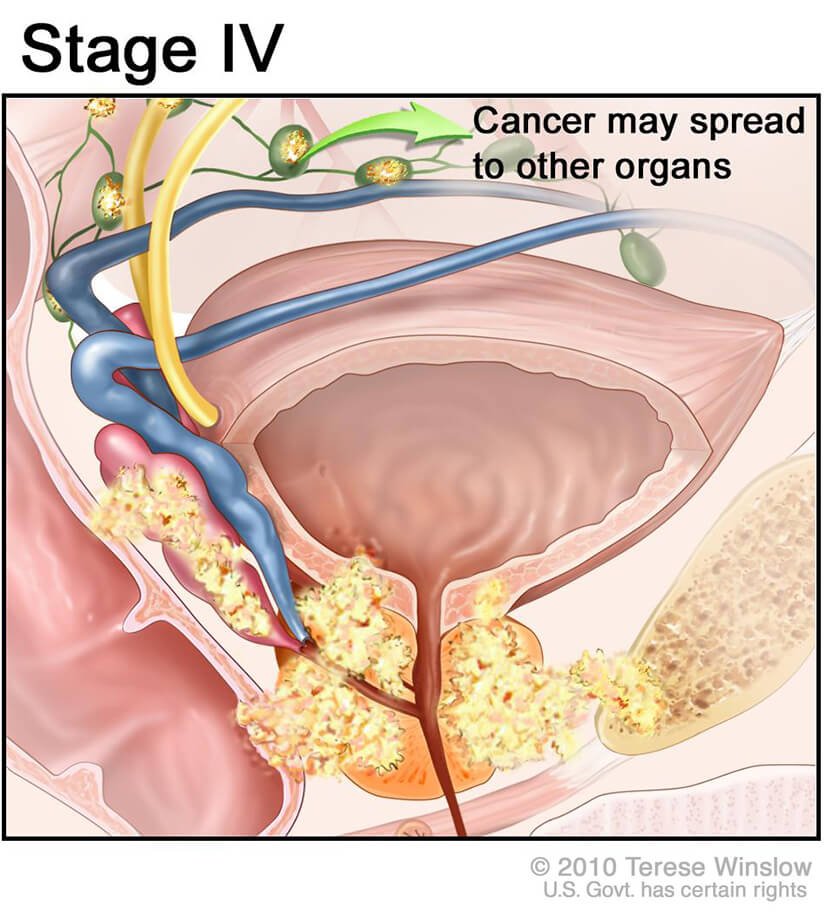

With the increasing use of highly effective hormone-blocking therapies for advanced prostate cancer, such as abiraterone (Zytiga®) and enzalutamide (Xtandi®), researchers have identified an emerging subtype of metastatic prostate cancer that is resistant to these therapies.

According to new research published October 9 in Cancer Cell, some metastatic prostate cancers can grow without the help of any type of signaling driven by androgens such as testosterone. Instead, the tumor cells appear to be using a cell-signaling pathway called the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) pathway.

“These cancers are definitely not static; they are continuing to evolve under the pressure of our treatments,” said Peter Nelson, M.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, one of the study’s lead authors.

The silver lining to their finding, Dr. Nelson explained, is that drugs that target the FGF pathway exist and have been tested in early-stage clinical trials.

“It’s kind of a bad news/good news situation: Although you’ve gone through one therapy and there are new drivers of these cancers, that also means there may be new [treatment] targets.”

Beyond Reliance on Androgen Receptors

Doctors treating patients with prostate cancer have long observed that tumors eventually develop resistance to hormone therapy, which disrupts the ability of androgens to help prostate cancer cells survive and grow.

This resistance occurs, it was thought, because prostate cancer cells developed mechanisms to turn these androgen receptor signaling pathways back on, explained Kathleen Kelly, Ph.D., chief of the Laboratory of Genitourinary Cancer Pathogenesis in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who was not involved in the study.

But since the introduction of the current generation of androgen-suppression therapies, doctors have been reporting that men appear to be developing metastatic tumors that do not rely on androgen receptor signaling, Dr. Kelly added.

To identify molecular pathways that allow prostate cancer cells to survive and grow without androgen receptor activity, Dr. Nelson and his colleagues began their research by using a variety of laboratory techniques to slowly deprive prostate cancer cells of the ability to use androgen receptor signaling.

They expected a type of androgen-independent prostate cancer cell, called neuroendocrine prostate cancer, to develop, explained Dr. Nelson. The development of neuroendocrine prostate tumors has previously been observed in men undergoing long-term hormone therapy.

Although the researchers did see some cells develop the molecular characteristics of neuroendocrine prostate tumors, to their surprise they saw more of a new type of resistance develop. These “double-negative” prostate cancer cells needed neither androgen receptor nor neuroendocrine signaling to survive.

Instead, by using a series of experimental approaches, the researchers found that the double-negative prostate cancer cells rely on FGF and a signaling pathway activated by FGF, called the MAPK pathway, for their growth.

When the research team treated the double-negative cells with drugs that block FGF or MAPK, the cells stopped growing and began to die. When they implanted FGF-driven prostate cancer cells into mice, treatment of the mice with an inhibitor of FGF signaling significantly reduced tumor growth compared with control mice that received no active therapy.

Unexpectedly, these cells did not seem to have any genetic changes that could explain their reliance on FGF and MAPK, explained Dr. Nelson. At this point, he said, it’s unclear how these resistant prostate cancer cells arise.

It may be due to epigenetic changes in the cells, or possibly because the cells have acquired the ability to use signaling molecules produced by the normal tissue around them (the microenvironment), said Dr. Nelson. The researchers have begun studies testing whether epigenetic changes play a role in this new type of treatment-resistant prostate cancer.

When the team performed similar experiments on metastatic prostate tumor samples collected from patients treated over a period of two decades (ending in 2016), they saw a pattern of resistance develop that was similar to what they’d observed in the laboratory.

When they looked at tumor samples collected before abiraterone and enzalutamide were in use, neuroendocrine prostate tumors were twice as prevalent as FGF-driven tumors. In samples taken from 2012 to 2016—after the drugs were approved by the Food and Drug Administration—FGF-driven tumors were approximately twice as common as neuroendocrine tumors.

“I think these [findings] will be a reference for everybody in the field in terms of thinking about how prostate cancer is changing,” commented Dr. Kelly.

Potential Future Treatment Strategies for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

The findings may have implications for trials of FGF inhibitors, Dr. Nelson said. For example, one FGF receptor inhibitor, dovitinib, has already been tested in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. The response rate for patients receiving the drug was modest. But, explained Dr. Nelson, this may be because most participants likely had tumors that could still use the androgen receptor pathway and weren’t totally dependent on FGF signaling.

For future trials targeting the FGF signaling pathway in patients with metastatic disease, “we’ll have to select these patients carefully,” said Dr. Nelson. Researchers will need to include patients with tumors “where it’s pretty clear that the androgen receptor pathway is off and the FGF pathway is on. We anticipate that they’d have a more robust response to therapy targeting that pathway.”

The ultimate approach for treating metastatic prostate cancer, he continued, may be to target more than one signaling pathway up front.

This strategy has recently become the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer that still depends on androgen signaling (hormone-sensitive prostate cancer), based on results from large studies including the CHAARTED, LATITUDE and STAMPEDE clinical trials.

These trials showed that men with hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer treated with standard androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) plus docetaxel or abiraterone live longer than men treated with standard ADT alone.

If studies show that FGF signaling pathway inhibitors extend survival in men with androgen-independent metastatic prostate cancer that is dependent on FGF signaling, the long-term strategy might be to incorporate FGF inhibitors as part of first-line therapy for metastatic disease instead of waiting for androgen resistance to develop, Dr. Nelson speculated.

“By not giving cells a chance to develop these other pathways, you might have better long-term outcomes,” he concluded.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario